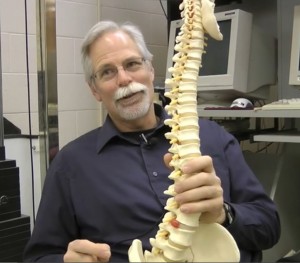

Last weekend I was fortunate enough to spend some quality time learning from one of the leading experts in lower back pain and rehabilitation, Dr Stuart McGill.

For those of you who know me well enough, you will know I picked up a horrendous lower back injury just over two years ago. In all seriousness, if it wasn’t for using the approach of Dr. McGill, I don’t think I would walking properly even now, let alone still be training.

So to cement some of the ideas into my head, here are 10 things I learnt from the weekend.

1. Principles guide the techniques you use…

There is no such thing as a “one size fits all” approach, nor a single exercise that acts as a pancea to the problems of back pain.

There are many causes, different types of pain, different underlying issues and many tools that can be used.

As a clinician/coach/trainer your guiding principle should always be to pick the safest and most effective route for the client/patient presented before you.

Balance risk vs reward. What are the most effective exercises and safest tools that can be used?

This will require adapting your approach as you progress with each case.

2. Remove bad movement habits first…

What causes the pain? Is it walking? Sitting? Standing posture?

Is how they bend over to pick something off the floor? Is it a lack of stability?

Begin by removing any bad movement habits that are sensitising the back to pain.

By removing the bad habits, you give the back a chance to settle and let pain subside. Over time this will build a capacity to begin exercising.

3. How disc injuries and subsequent pain occurs.

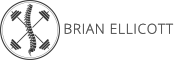

The discs are similar in appearance to a sliced onion, in that they have a central nucleus, surrounded by the layers of the annulus – much like the layers in an onion.

As the disc is compressed from poor movement habits over a number of years, the nucleus is slowly pushed through the layers, until eventually it reaches the outer layer causing a disc bulge.

It is then you are at risk of serious injury – the final straw that breaks the camel’s back (literally) as as spinal nerve becomes compressed.

4. How the discs and vertebrae work to absorb compression.

Dr McGill showed us some great footage of some of his team’s studies in the lab.

One study involved compressing a vertebra with force inside a specialised machine. As pressure was applied, blood was driven out of the vertebra as it was compressed.

This demonstrated that the discs in your back act as the oil filled shock absorbers in your car’s suspension – slowing the forces travelling through the spine.

While the bony vertebra can be compressed to absorb the actual force itself, much like the springs on suspension do.

5. The spine will adapt its properties over time.

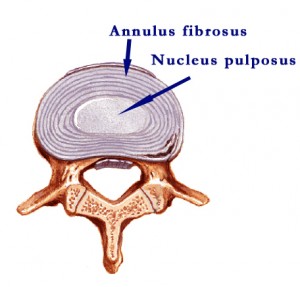

By studying the spines of long-term weight lifters, Dr. McGill has been able to observe the adaptations the spine can go through in response to the structural demands placed by lifting heavy weights. By thickening certain parts of the vertebra (transverse processes), the spine is then able to withstand much greater force.

In older patients (60-70+) he has noted that old disc injuries, that were painful to the patient in their 30’s and 40’s, have gristled and set and are now no longer painful because the joint is now more stable.

6. Be precise in your quality of work…

In order to free yourself from back pain you must be mindful in your practice of rehabilitation exercises.

Perform them when you are fresh mentally and pay close attention to the small details and any movement compensations.

Dr. McGill also advocates the Russian Descending Pyramid of sets and reps. Â Whereby you reduce the amount of reps (usually by 2) each set.

For example on the Bird-dogs, you may perform 6 reps on the first round, 4 on the second and 2 on the last.

This allows you to build muscular endurance without going to absolute failure. This prevents ingraining sloppy movement habits as fatigue sets in and also ensures that your recovery will not be hampered by pushing too far.

7. Your hip structure dictates how deep you can squat and the safest technique.

One of the biggest, repeated arguments on the internet is how deep should people squat?

I’ve always been of the “depends” camp – with a mind to risk vs reward.

It was great to finally learn why some people can and should squat deep, whereas for others, deep squatting will increase the risk lower back injury.

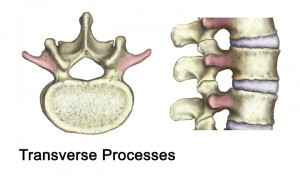

It all comes down to the depth of your hip socket.

Over 30 years of working world class athletes and the general public, Dr. McGill has observed differences in hip structure that can be traced back to your genetic heritage.

He has noted that those with an eastern european background (Croatia, Poland and Western Russia) have a genetic tendency towards what is know as “Dalmation Hip”. A very shallow hip socket, that allows for a greater range of motion but also has a higher risk of hip dysplasia.

This in turn gives them an advantage in the deep squat movement required for safe, high level olympic lifting. Hence why so many world class lifters come from those areas.

If, like me, your genetic heritage is from western Europe, Scotland or Ireland – you’ll have a tendency towards “Celtic Hip”, which means you have a deeper hip socket and should avoid deep squats under load.

8. Progression is key…

Most techniques, plans and exercises will have a positive effect for around two weeks.

After that, a clever use of program progression is required.

Always build towards the long-term goals of the client:

Do they want to return to sport?

Improve athletic performance?

Not put their back out picking up their baby from the crib at 3am in the morning?

Be able to sit for 8 hours a day at work without getting crippled?

Dr McGill advocates developing their lower back and core performance as far as you can.

Build them a safe margin of error – you never know what life will throw at them.

9. Tailor  performance to the athlete and their sport

Always structure the program to enhance and tune the abilities of the athlete and the specific requirements of their sport.

One example of this involves rehabilitating athletes whose chosen sport requires a left/right imbalance of work and development.

Tennis and golf are great examples of this.

If the athlete presents with major differences between the left and right side of their body, should you aim to balance them completely out?

Be careful, you may just de-tune their technique and ruin them for their sport.

10. When coaching athletes to develop strength, are you really coaching strength?

Dr. McGill finished weekend with a workshop on developing the neurological drive of athletes to produce maximal strength.

One of his biggest points here was that modern strength coaching has become too polluted with a bodybuilding style approach, which hinders the development of athletic performance by de-tuning the neurological drive of athletes.

Create and develop the “spark” of maximal neurological drive, don’t just bury athletes with sets and reps…